Most people think patents are the only thing protecting drug prices. If a patent expires, generics rush in, prices drop, and everyone wins. But that’s not how it works anymore. In reality, many blockbuster drugs stay off-limits to generics for over 15 years-even after their core patent dies. That’s not magic. It’s market exclusivity extensions, a complex web of regulatory rules that let drugmakers stretch their monopolies long after patents expire.

Patents Aren’t the Whole Story

A standard patent lasts 20 years from the date it’s filed. But for drugs, that clock starts ticking long before the medicine even hits the market. Clinical trials take 7-10 years. The FDA review adds another 1-3. By the time a drug is approved, you might have only 5-8 years of actual patent life left. That’s not enough to recoup billions spent on R&D. That’s where exclusivity extensions come in. They’re not patents. They’re legal protections granted by the FDA or EMA, separate from the patent system. Think of them as regulatory timeouts-extra years where no generic can legally enter the market, even if the patent is gone.The U.S. System: A Stack of Locks

In the U.S., there are five main types of exclusivity that can pile on top of each other:- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years. This is the baseline. If your drug contains a brand-new active ingredient, no generic can even submit an application for five years.

- Orphan Drug exclusivity: 7 years. For drugs treating rare diseases (fewer than 200,000 U.S. patients). Even if there’s no patent, this blocks generics.

- New Clinical Investigation exclusivity: 3 years. For new uses of existing drugs. But here’s the catch: the FDA now demands proof the new use offers real clinical benefit-not just a tweak.

- Pediatric exclusivity: 6 months added to any existing exclusivity. To get it, companies must complete FDA-requested studies in children. It’s not free-it costs millions-but it can delay generics by half a year, which means billions in extra revenue.

- 180-day exclusivity for first generic filer: This one’s tricky. It’s meant to reward the first company to challenge a patent, but it’s often used strategically to delay other generics.

The real power? Stacking. A drug can have NCE exclusivity (5 years) + pediatric extension (6 months) + orphan exclusivity (7 years) + patent term extension (up to 5 years). The result? A drug might face zero generic competition for 17+ years.

Europe’s Approach: Longer, But Less Stackable

The EU uses a different model. Instead of multiple exclusivity types, they rely heavily on the Supplemental Protection Certificate (SPC). An SPC can extend protection up to 15 years after drug approval-sometimes longer if pediatric studies are done. That’s one extension, not five.But the EU also has orphan drug exclusivity: 10 years, extendable to 12 if pediatric data is submitted. And they’ve recently tightened rules to stop companies from getting double protection-unlike the U.S., where stacking is common and legal.

Still, the result is similar: drugs stay expensive. For example, a drug with a 20-year patent and a 12-year SPC can have nearly 30 years of protection from the time it’s invented.

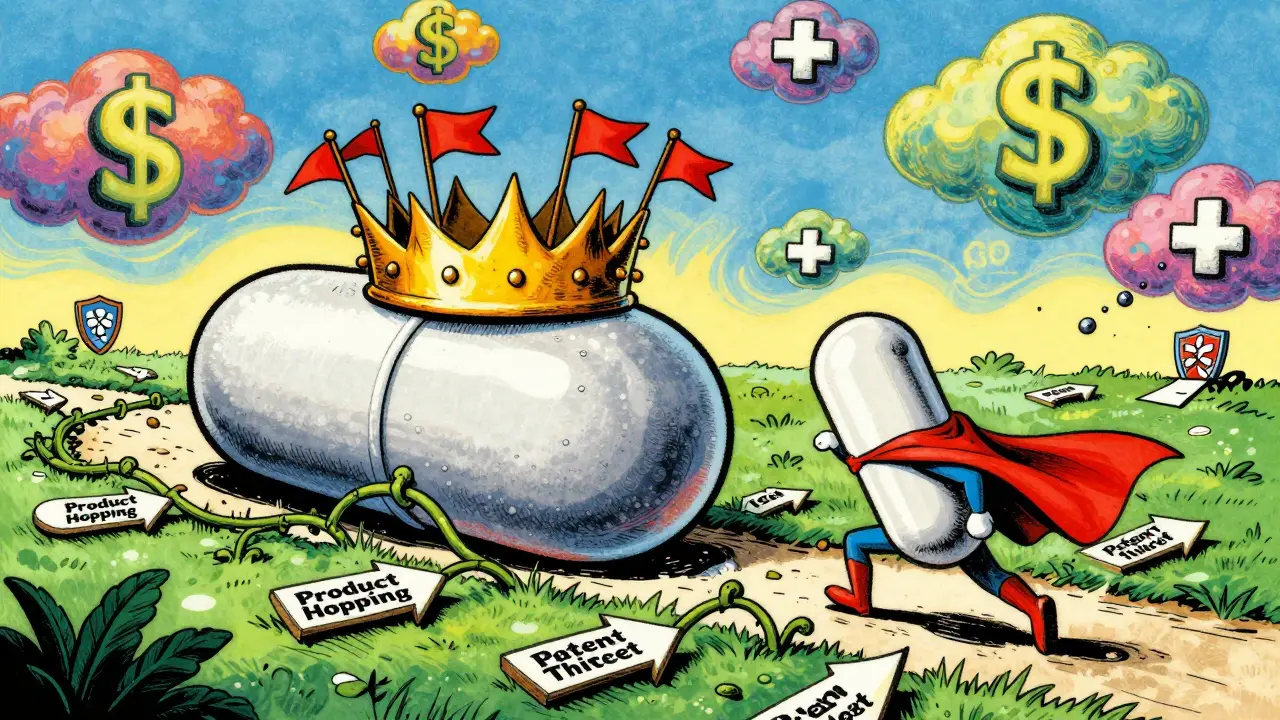

How Companies Game the System

It’s not just about filing for exclusivity. It’s about timing, tricks, and tactics.One big strategy is patent thickets. Companies file dozens of secondary patents on tiny changes: a new tablet coating, a different dosing schedule, a new delivery device. The core drug might be off-patent, but these secondary patents keep generics out. The drug tazarotene had 48 secondary patents filed after its original one. That’s not innovation-it’s legal obstruction.

Then there’s product hopping. Just before a patent expires, a company launches a slightly modified version-say, a pill that dissolves faster or a new inhaler. They market it as “improved,” and doctors switch patients over. Generics can’t copy the new version until its patent expires. Teva reported this tactic delayed generic entry for 17% of their target drugs.

And let’s not forget delayed patent filing. Some companies wait until after Phase II trials to file their main patent. That way, the 20-year clock starts later, giving them more time to profit before generics show up.

Why It Matters: Billions on the Line

These extensions aren’t theoretical. They cost real money.A 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum looked at four top-selling drugs: bimatoprost, celecoxib, glatiramer, and imatinib. Without exclusivity extensions, generic competition would’ve saved patients and insurers $3.5 billion over just two years. That’s not a typo. Four drugs. Two years. $3.5 billion.

In 2022, branded drugs made up 78% of U.S. pharmaceutical revenue-even though they accounted for only 10% of prescriptions. Why? Because exclusivity keeps them priced high.

For companies, it’s simple math. The average cost to develop a new drug is $2.3 billion. Without exclusivity, that investment can’t be recovered. But for patients, it’s a different story. Many can’t afford the $10,000-a-month price tag when a generic version could cost $200.

Who Benefits? Who Gets Left Behind?

The system was designed to encourage innovation-especially for rare diseases. And it works. Orphan drug approvals jumped from 201 in 2010 to 1,027 in 2022. That’s progress. Treatments for diseases once ignored now exist because exclusivity made them financially viable.But here’s the problem: the same tools that help rare disease patients are also used to protect blockbuster drugs for common conditions like high blood pressure or diabetes. A drug for a disease affecting 50 million people gets the same 7-year orphan exclusivity as one for a disease affecting 500. That’s not what the law intended.

And while startups say exclusivity helps them raise venture capital, big pharma uses it to lock in profits. Of the top 20 pharmaceutical companies, 100% have dedicated teams just to manage exclusivity. Some teams have 20+ people focused on nothing but delaying generics.

The Pushback Is Growing

Regulators are starting to push back.In 2023, the FDA tightened rules for 3-year exclusivity. Now, companies must prove a new use isn’t just a minor tweak-it has to show real clinical benefit. No more “we changed the color of the pill” loopholes.

The FTC filed a legal brief arguing that product hopping violates antitrust laws. And the European Commission is considering reforming the SPC system to reward true innovation, not minor changes.

But change is slow. The average effective market exclusivity for new drugs rose from 12.7 years in 2018 to an expected 16.3 years by 2028. That’s not just extension. That’s entrenchment.

What’s Next?

The tension between innovation and access won’t disappear. Drugmakers will keep finding ways to stretch exclusivity. Regulators will keep trying to close loopholes. Patients will keep paying more.But awareness is growing. More lawmakers, insurers, and even some doctors are asking: Is this system still serving the public? Or has it become a tool for profit at the cost of affordability?

For now, the answer is clear: patents are just the beginning. The real battle for drug prices happens in the fine print of regulatory rules. And those rules? They’re written by lawyers, not doctors.

What’s the difference between a patent and market exclusivity?

A patent is a legal right granted by the USPTO to protect an invention-for drugs, that’s usually the chemical compound. It lasts 20 years from filing. Market exclusivity is granted by the FDA or EMA and blocks generics from entering the market for a set time, regardless of patent status. Exclusivity can exist even if there’s no patent, and it’s often longer than the remaining patent life.

Can a drug have both a patent and exclusivity at the same time?

Yes, and most do. In fact, that’s the norm. A drug might have a 20-year patent, a 5-year NCE exclusivity, a 7-year orphan exclusivity, and a 6-month pediatric extension. These protections run at the same time or one after another. The last one to expire determines when generics can enter.

Why does pediatric exclusivity add 6 months?

It’s an incentive. The FDA asks drugmakers to test their medicines in children, because many drugs are prescribed to kids without proper pediatric data. If the company completes the requested studies, they get 6 months added to any existing exclusivity-patent or regulatory. It’s not free; it costs millions in clinical trials. But for a blockbuster drug, 6 months can mean $1 billion in extra revenue.

Do all countries use the same exclusivity rules?

No. The U.S. allows stacking multiple exclusivities. The EU uses fewer types but longer individual periods. The EU’s SPC can extend protection up to 15 years after approval, while the U.S. caps patent term extensions at 14 years after approval. The EU also has stricter rules against double protection, while the U.S. system is more permissive.

How do generics finally get approved if exclusivity is still active?

They can’t-until every exclusivity period expires. Generic companies must wait until the last protection ends. Some challenge patents in court, hoping to invalidate them early. Others wait for exclusivity to run out. In rare cases, the FDA may grant an exception if a drug is in short supply, but that’s the exception, not the rule.

Are exclusivity extensions only for big pharma?

No. While big companies use them most aggressively, small biotech firms rely on them too. For startups developing drugs for rare diseases, orphan exclusivity can be the only reason investors will fund them. Without it, many life-saving treatments for small patient groups wouldn’t exist. The problem isn’t the system itself-it’s how it’s used for profitable, common diseases.

Monte Pareek

December 18, 2025 AT 00:01Let me break this down real simple - patents are just the tip of the iceberg. The real game is in the FDA’s backroom deals and corporate loopholes. Companies aren’t innovating they’re lawyering. A 5-year NCE? Sure. But stack it with orphan status for a common disease like hypertension? That’s not medicine that’s market manipulation. And don’t get me started on pediatric extensions - $1 billion for six months because some kid got tested? That’s not progress that’s profit theater. The system was built to help rare disease kids now it’s propping up billion-dollar brands for high blood pressure pills. This isn’t broken it’s by design.

holly Sinclair

December 19, 2025 AT 15:24It’s wild how we’ve turned healthcare into a legal engineering problem instead of a medical one. We’re not debating efficacy or safety anymore we’re debating which regulatory clause gets to block a generic. The 180-day exclusivity for first filers? It was meant to incentivize challenge but now it’s a delay tactic - one company gets a head start and then just sits on it while others wait. And the patent thickets? Forty-eight patents on a drug that’s basically the same molecule with a different coating? That’s not innovation that’s litigation arbitrage. We’ve created a system where the most skilled lawyers win not the best scientists. And the worst part? We call it progress. What happened to the idea that medicine should be about healing not holding patents hostage?

mark shortus

December 20, 2025 AT 16:08OH MY GOD. I JUST REALIZED - THEY’RE STUFFING OUR MEDS WITH LEGAL TRAPS LIKE A BURGER WITH 17 LAYERS OF CHEESE AND NO MEAT. 17 YEARS? 30 YEARS? THIS ISN’T DRUG DEVELOPMENT THIS IS A CORPORATE TIME MACHINE. I WANT TO SCREAM. I WANT TO CRY. I WANT TO BURN THE FDA’S BUILDING DOWN. WHY DOES A DRUG FOR DIABETES GET THE SAME PROTECTION AS ONE FOR A DISEASE THAT ONLY 500 PEOPLE HAVE? WHO WROTE THIS RULES? A LAWYER WHO WANTS A YACHT? I’M NOT EVEN JOKING. I’M SO ANGRY RIGHT NOW I CAN’T EVEN TYPE PROPERLY. THIS IS A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY.

Elaine Douglass

December 21, 2025 AT 13:46My uncle just got prescribed one of those drugs and he’s on a fixed income. He pays $800 a month for something that could be $150. I just cried reading this. I didn’t even know this stuff was happening. Thank you for explaining it so clearly. I feel like I finally understand why my family is drowning in medical bills. This isn’t just about big pharma - it’s about people like us being left behind.

Takeysha Turnquest

December 23, 2025 AT 11:01They’re not selling medicine they’re selling time. Time is the only real currency here. Every day that generic is delayed is another day the rich get richer and the sick get poorer. We’ve turned life into a countdown clock and the only ones holding the timer are the ones who already own the clock. This isn’t capitalism this is feudalism with pill bottles.

Jedidiah Massey

December 23, 2025 AT 11:26Let’s be clear - the SPC framework in the EU is structurally superior to the U.S. stacking model. The EU’s SPC + pediatric extension creates a single, transparent extension horizon whereas the U.S. employs a multiplicative regulatory arbitrage paradigm that obfuscates true market entry timelines. The FTC’s antitrust intervention on product hopping is a necessary but insufficient intervention. What’s needed is a patent-exclusivity decoupling mechanism to prevent rent-seeking behavior. Also - 🤷♂️

Edington Renwick

December 24, 2025 AT 01:56People act like this is new. It’s not. Every industry with high fixed costs and low marginal costs does this. Pharma’s just the most visible because people die without the pills. But the real issue? The public doesn’t understand that innovation requires profit. If you kill exclusivity you kill future drugs. The question isn’t whether this is unfair - it’s whether you’d rather have no treatment at all for rare diseases or pay a little more so someone else’s kid gets a shot. The answer’s obvious if you’re not emotionally reactive.

Allison Pannabekcer

December 24, 2025 AT 21:44I think we need to separate the good from the bad here. Orphan drug exclusivity saved my cousin’s life - she has a disease that affects 1 in 500,000. Without that 7-year protection, no company would’ve touched it. But you’re right - using the same tool for a drug that 10 million people take? That’s wrong. Maybe we need tiered exclusivity - longer for rare diseases shorter for common ones. Or maybe cap total exclusivity at 12 years no matter how many boxes you check. We don’t have to throw the baby out with the bathwater. We just need to fix the plumbing.

Sarah McQuillan

December 26, 2025 AT 15:41Actually the U.S. system is the most fair. Europe’s SPC is just protectionism disguised as innovation. We reward real risk-taking. If you spend $2 billion and get a drug approved you deserve to make your money back. The rest of the world just wants to free-ride. And don’t even get me started on how other countries steal our drugs and resell them. This isn’t greed - it’s survival. If we don’t protect our companies we lose the next breakthrough. And no - generics aren’t ‘just as good’ - they’re cheaper copies. Sometimes they’re not even bioequivalent. So stop crying about price and thank the system that gave you the medicine in the first place.