Ever wonder why a pill you swallow can stop a headache, calm your nerves, or fight an infection? It’s not magic. Medicines work because they’re designed to interact with your body at a molecular level - like a key fitting into a lock. But not all keys work the same way, and not all locks are safe to force open. Understanding how medicines work isn’t just for doctors. It’s the foundation of using them safely.

How Medicines Actually Work in Your Body

Every medicine is a chemical compound. Once you take it - whether swallowed, injected, or applied to your skin - it travels through your bloodstream until it finds its target. That target is usually a specific protein, enzyme, or receptor on a cell. These targets are like tiny switches that control bodily functions: pain signals, inflammation, heart rate, mood, even how your cells grow. Take aspirin. It blocks an enzyme called COX-1, which your body uses to make chemicals that cause pain and swelling. By turning off that enzyme, aspirin reduces pain and fever. It’s not numbing your nerves; it’s stopping the signal before it starts. Antibiotics like penicillin work differently. They don’t touch your cells. Instead, they attack bacteria by breaking down their cell walls. Think of it like popping a balloon - the bacteria burst because they can’t hold their shape anymore. Your body’s cells? They’re built differently, so they’re left unharmed. Then there are drugs like fluoxetine (Prozac), an SSRI. These don’t add more serotonin to your brain. They block the pumps that pull serotonin back into nerve cells after it’s been released. That keeps more serotonin floating around, helping stabilize mood. It’s not flooding your system - it’s keeping what’s already there from being swept away too quickly. This is called the mechanism of action. It’s the exact science behind how a drug produces its effect. Knowing this isn’t academic - it’s what tells doctors whether a drug will work for you, how much to give, and what might go wrong.Why Your Body’s Design Matters for Safety

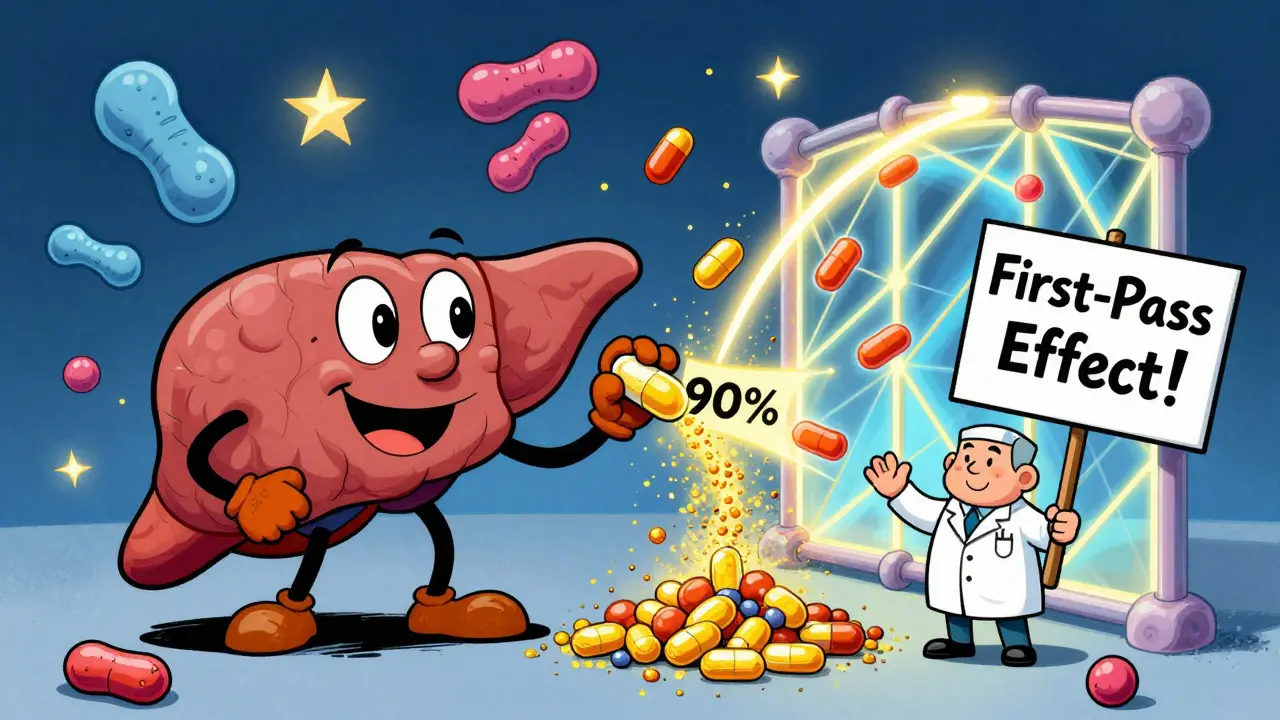

Your body isn’t just a container for medicine. It’s a complex system that changes how drugs behave. The same pill can act very differently in different people. When you swallow a tablet, it goes through your stomach and intestines. Some drugs are absorbed right there - like antacids that neutralize stomach acid. Others need to pass through the gut wall into your blood. But here’s the catch: your liver doesn’t wait for the drug to reach its target. It starts breaking it down before it even circulates. This is called the first-pass effect. For drugs like morphine or propranolol, up to 90% of the dose can be destroyed before it ever gets to work. That’s why some pills have to be given in higher doses or injected instead. Then there’s protein binding. Most drugs in your blood stick to proteins like albumin. Only the small fraction that’s floating free can interact with your cells. Warfarin, a blood thinner, is 99% bound to proteins. That means if another drug comes along that also binds to those proteins - like certain antibiotics - it can kick warfarin loose. Suddenly, you’ve got way more active warfarin in your blood than intended. That’s when bleeding risks spike. The blood-brain barrier is another gatekeeper. It’s designed to protect your brain from toxins. But that means most drugs can’t get in. Parkinson’s patients take levodopa, not dopamine, because dopamine can’t cross the barrier. Levodopa is a chemical cousin that can slip through, then gets converted into dopamine inside the brain. Without that design, the drug wouldn’t work at all.

When Medications Are Safe - And When They’re Not

Safety doesn’t mean “no side effects.” It means knowing the risks and managing them. A drug can be perfectly safe if used correctly, and dangerous if misused. Lithium, used for bipolar disorder, is a classic example. It’s effective - but the line between a helpful dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. Blood levels must stay between 0.6 and 1.2 mmol/L. Too low, and it doesn’t work. Too high, and you get tremors, confusion, even kidney damage. That’s why people on lithium get regular blood tests. It’s not just monitoring - it’s survival. Warfarin users face similar challenges. It interferes with vitamin K, which your body needs to make clotting factors. So eating a big salad with spinach or kale - which are packed with vitamin K - can make warfarin less effective. On the flip side, skipping your greens for a week can make your blood too thin. Patients who understand this link report fewer emergencies. One Reddit user wrote: “I used to panic every time I ate kale. Now I just adjust my dose with my pharmacist. It’s a balance, not a fear.” Even over-the-counter drugs aren’t risk-free. Mixing NSAIDs like ibuprofen with blood pressure meds can reduce the meds’ effectiveness. Taking acetaminophen with alcohol increases liver damage risk. These aren’t myths - they’re documented interactions backed by decades of data.Why Understanding Your Drug Can Save Your Life

A 2023 study from PatientsLikeMe found that 68% of users worried about side effects - and 42% said they’d feel safer if they understood how their medicine worked. That’s not a coincidence. People prescribed trastuzumab (Herceptin) for breast cancer were 78% more likely to recognize early signs of heart trouble - a known side effect - if they knew the drug targeted HER2 proteins. Those who didn’t understand the mechanism often dismissed chest tightness as stress or fatigue. By the time they sought help, damage was often advanced. Statins, used to lower cholesterol, cause muscle pain in some users. That pain is a warning sign. If you know statins block HMG-CoA reductase - the enzyme your liver uses to make cholesterol - you also know that muscle cells rely on the same pathway. Muscle pain isn’t just a nuisance; it could be early rhabdomyolysis, a rare but life-threatening breakdown of muscle tissue. Patients who understood this were 3.2 times more likely to report the symptom early and avoid hospitalization. Even the way a drug is explained matters. Pharmacists who use analogies - like comparing SSRIs to “putting a cork in the serotonin recycling tube” - see 42% better patient recall, according to a 2023 survey by the American Pharmacists Association. Simple language saves lives.

The Future: Personalized Safety Through Mechanism

The future of medication safety isn’t just about better drugs - it’s about better matching drugs to people. The NIH’s All of Us program is collecting genetic data from a million people to see how individual differences affect drug response. We already know that 28% of bad reactions are tied to gene variants that change how drugs are processed or how receptors respond. One person might need half the dose of a drug because their liver breaks it down slowly. Another might need double because their receptors barely bind to it. By 2028, early trials suggest we’ll have “digital twins” - computer models of your body that simulate how a drug will behave in you. These models will factor in your genes, age, liver function, and even gut bacteria. Imagine taking a virtual pill before the real one - and seeing if it causes a reaction, lowers your blood pressure, or triggers muscle pain - all before you swallow a single tablet. Right now, 30% of prescribed medications still lack a fully understood mechanism. That’s why over 1.3 million Americans end up in emergency rooms every year from adverse drug events. We’re not just guessing anymore. We’re learning - and that’s changing everything.What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a science degree to use medicine safely. But you do need to ask the right questions:- What is this medicine supposed to do in my body?

- What are the most common side effects - and which ones mean I should call my doctor?

- Are there foods, drinks, or other meds I need to avoid?

- Is there a blood test or monitoring I need?

How do medicines know where to go in my body?

Medicines don’t "know" where to go - they’re carried by your bloodstream and interact with specific targets based on their chemical shape. Think of it like a key fitting into a lock. Only cells with the right receptor will respond. For example, insulin only works on cells that have insulin receptors. Drugs that need to reach the brain, like those for Parkinson’s, are specially designed to cross the blood-brain barrier. Others, like stomach meds, act right where they’re absorbed.

Why do some drugs need blood tests?

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like lithium, warfarin, or certain seizure medications - have a tiny gap between the dose that helps and the dose that harms. Blood tests measure how much of the drug is in your system to make sure you’re in the safe range. For lithium, the target is 0.6-1.2 mmol/L. Even small changes in kidney function or diet can push levels out of range, so regular monitoring is critical.

Can I stop taking my medicine if I feel better?

Not always. Antibiotics must be taken for the full course to kill all the bacteria - stopping early lets resistant strains survive. Antidepressants like SSRIs take weeks to build up in your system, and quitting suddenly can cause withdrawal symptoms like dizziness or brain zaps. Even if you feel fine, your body may still need the drug to stay balanced. Always talk to your doctor before stopping.

Are natural supplements safer than prescription drugs?

No. Many supplements aren’t tested for safety or interactions like prescription drugs. St. John’s Wort, for example, can reduce the effectiveness of birth control, antidepressants, and even heart meds. Garlic supplements can thin your blood, which is dangerous if you’re on warfarin. Just because something is "natural" doesn’t mean it’s safe - especially when mixed with other medicines.

What should I do if I miss a dose?

It depends on the drug. For antibiotics, take it as soon as you remember - unless it’s almost time for the next dose. For blood pressure meds, skip the missed dose and wait for the next one. Never double up unless your doctor says to. For drugs like warfarin or insulin, missing a dose can be risky. Always check the patient leaflet or call your pharmacist. They’re trained to handle these questions.

If you’re taking any medication - even one you’ve had for years - take a moment to ask: "Do I know how this works?" That simple question is the first step to using your medicine safely, effectively, and with confidence.

Edith Brederode

January 21, 2026 AT 02:21Emily Leigh

January 21, 2026 AT 02:22Art Gar

January 22, 2026 AT 07:17clifford hoang

January 23, 2026 AT 13:20Arlene Mathison

January 23, 2026 AT 17:22Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 24, 2026 AT 05:43Greg Robertson

January 24, 2026 AT 20:35Crystal August

January 25, 2026 AT 06:59Nadia Watson

January 27, 2026 AT 01:14Courtney Carra

January 27, 2026 AT 06:40thomas wall

January 27, 2026 AT 21:37Shane McGriff

January 28, 2026 AT 23:11Art Gar

January 29, 2026 AT 14:39