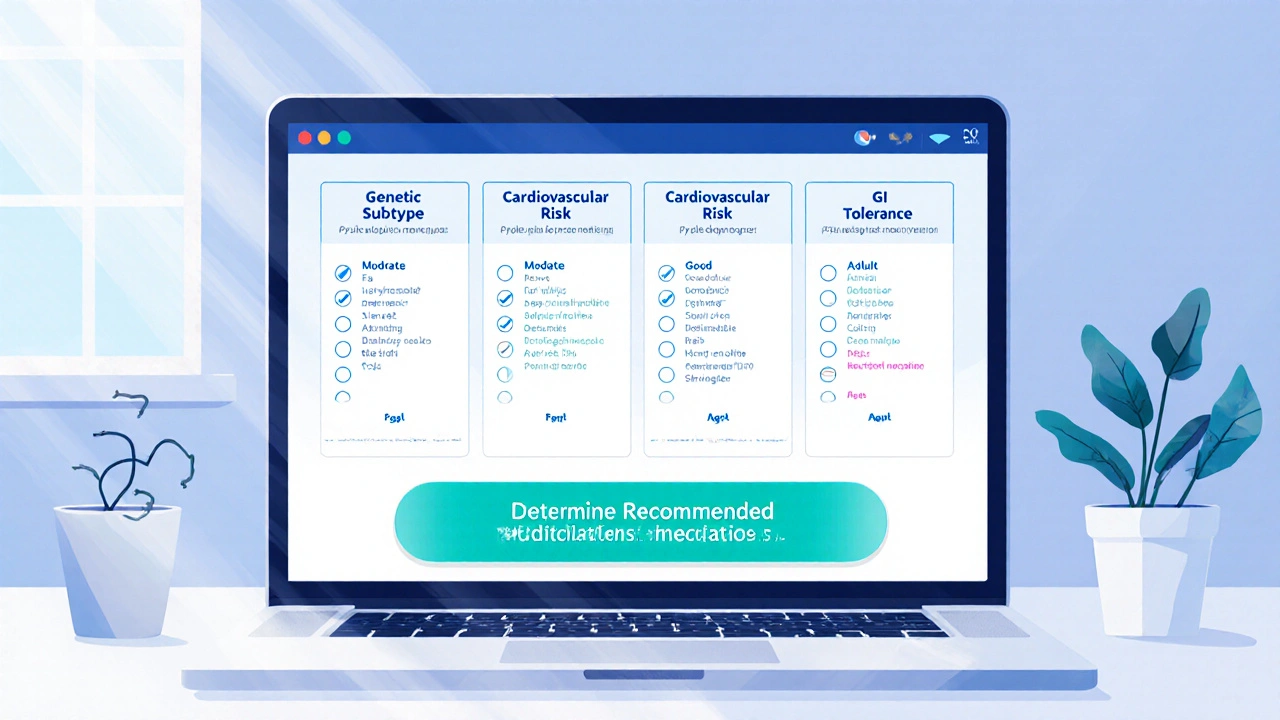

Polyposis Medication Selector

Enter your details and click "Determine Recommended Medications" to see personalized recommendations.

When you hear the word Polyposis is a group of conditions marked by the growth of dozens to thousands of polyps in the colon or other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, the first thought is often surgery. While removing polyps surgically saves lives, a growing body of research shows that the right meds can shrink, slow, or even prevent new polyps from forming. This article walks you through why drugs matter, which ones work best, and how to fit them into a broader treatment plan.

TL;DR

- NSAIDs like Sulindac and COX‑2 inhibitors (e.g., Celecoxib) cut polyp count by 40‑60% in many patients.

- Aspirin, taken daily at low dose, shows long‑term chemopreventive benefits for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

- Drug choice depends on genetic subtype, polyp burden, side‑effect tolerance, and surgeon’s plan.

- Regular monitoring (colonoscopies, blood tests) remains essential even on medication.

- Emerging agents such as EGFR inhibitors and selective Wnt pathway modulators are in clinical trials.

Understanding Polyposis and Its Variants

Polyposis isn’t a single disease. The most common hereditary form is Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), caused by APC gene mutations and characterized by hundreds of adenomatous polyps. Gardner syndrome is a FAP variant that adds extra‑colonic tumors. Peutz‑Jeghers syndrome (PJS) involves hamartomatous polyps and mucocutaneous pigmentation, driven by STK11 mutations. Each subtype carries a different cancer risk profile, which shapes medication strategy.

Why Medications Matter Beyond Surgery

Even the most experienced colorectal surgeon can’t remove every tiny polyp, especially when they’re scattered throughout the colon. Untreated polyps can become malignant, and repeated surgeries increase scar tissue and complications. Medications act as a “chemical scalpel” that:

- Reduce polyp size, making endoscopic removal easier.

- Slow new polyp formation, buying time before definitive surgery.

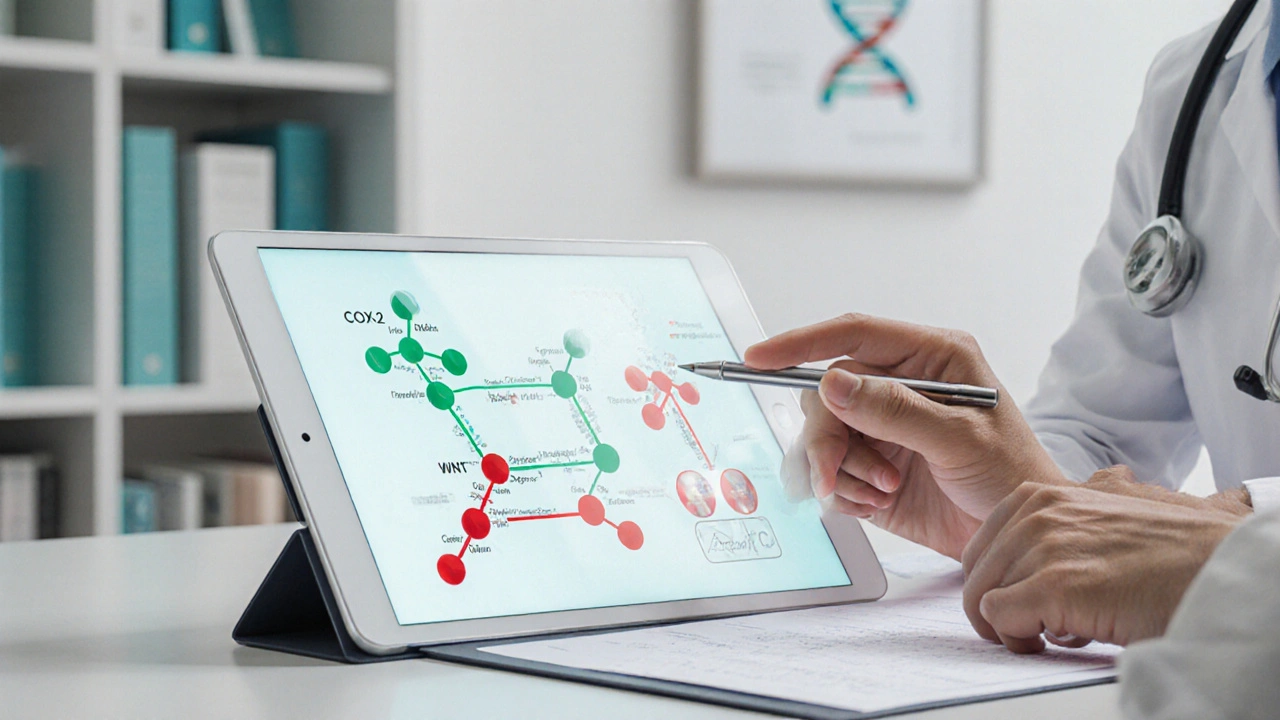

- Target molecular pathways (e.g., COX‑2, Wnt) that drive polyp growth.

Clinical trials from 2018‑2024 consistently report a 30‑70% reduction in polyp burden with appropriate drug regimens.

Main Classes of Drugs Used in Polyposis

Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the workhorse. They inhibit cyclo‑oxygenase enzymes, which in turn lower prostaglandin‑E2-a molecule that fuels polyp growth.

- Sulindac (dose150mg bid) achieved a 45% average reduction in polyp count over 12months in a 2022 multicenter study.

- Aspirin low‑dose (81mg daily) lowered colorectal cancer risk by 25% after 5years in FAP patients (2021 data).

- Selective COX‑2 inhibitors like Celecoxib (200mg bid) cut polyp size by up to 60% but carry cardiovascular warnings.

Other agents explore the same pathway from different angles. Mesalazine (an aminosalicylate) shows modest anti‑inflammatory effects but limited clinical data for polyposis.

Choosing the Right Drug: Decision Criteria

Not every patient can take every drug. Here’s a quick checklist doctors use:

- Genetic subtype: APC mutations respond best to NSAIDs; STK11‑related PJS may need different targets.

- Cardiovascular risk: Avoid COX‑2 inhibitors in patients with hypertension or prior heart disease.

- Gastro‑intestinal tolerance: History of ulcers steers you toward low‑dose aspirin or mesalazine.

- Age and fertility plans: Some NSAIDs can affect sperm quality; discuss with reproductive‑health specialists.

- Planned surgery timeline: If surgery is imminent (within 6months), short‑term high‑dose sulindac may be preferred.

Collaborative decision‑making-patient, gastroenterologist, genetic counselor, and surgeon-produces the safest, most effective plan.

Managing Side Effects and Monitoring

Every drug class brings its own risk profile. Below are practical ways to stay ahead:

- NSAIDs (Sulindac, Aspirin): Watch for gastrointestinal bleeding. Use proton‑pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole) if ulcer risk is high.

- COX‑2 inhibitors: Baseline ECG and lipid panel; repeat every 6months.

- Mesalazine: Check renal function quarterly, as rare nephrotoxicity can occur.

Standard monitoring schedule includes colonoscopy every 12‑24months, CBC, liver function tests, and a focused questionnaire on abdominal pain or black stools.

Emerging Therapies on the Horizon

Research is moving beyond COX inhibition. A few promising candidates:

- Wnt pathway modulators: Drugs like LGK974 (a porcupine inhibitor) are in PhaseII trials for FAP, showing up to 70% polyp regression.

- EGFR inhibitors: Low‑dose cetuximab combined with NSAIDs may synergistically block growth signals (pilot study 2023).

- Immunomodulators: Low‑dose methotrexate is being explored for its anti‑inflammatory effect on hamartomatous polyps in PJS.

These agents aren’t widely available yet, but keeping an eye on clinicaltrials.gov can help patients access compassionate‑use programs.

Practical Checklist for Patients and Clinicians

- Confirm genetic diagnosis (APC, STK11, MUTYH) before starting any drug.

- Discuss cardiovascular and GI risk factors with your doctor.

- Start with the lowest effective dose; titrate based on colonoscopic findings.

- Schedule baseline labs (CBC, LFTs, renal panel) and repeat every 3‑6months.

- Maintain a medication diary to capture side effects early.

- Plan colonoscopy intervals according to drug response-more frequent if polyps persist.

Key Takeaways

Medications are no longer an afterthought in polyposis care; they’re a central pillar that can delay or even reduce the need for major surgery. The most evidence‑backed options-polyposis medications like sulindac, aspirin, and celecoxib-offer sizable polyp shrinkage when matched to the right patient profile. Ongoing monitoring and a clear side‑effect management plan keep the benefits outweighing the risks. And as new targeted agents move through trials, the future looks brighter for anyone living with this lifelong condition.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I stop taking NSAIDs if my polyps disappear?

Stopping abruptly is not advised. Even if colonoscopy shows few or no polyps, the underlying genetic drive remains. Doctors usually taper the dose and continue low‑dose therapy for the long term, unless side effects become intolerable.

Is aspirin safe for teenagers with FAP?

Low‑dose aspirin (81mg) is generally well‑tolerated in adolescents, but a pediatric gastroenterologist should evaluate bleeding risk first. Regular blood‑work and a stool‑occult test are recommended.

What if I have a history of heart disease? Can I still use celecoxib?

Celecoxib carries a higher cardiovascular risk, especially at doses above 200mg daily. Patients with prior heart attacks, stroke, or uncontrolled hypertension should avoid it and discuss alternative NSAIDs with their doctor.

How often should I get a colonoscopy while on medication?

Most guidelines suggest a colonoscopy every 12months for high‑risk FAP patients, even if drugs are effective. If the polyp burden drops dramatically, your doctor may extend the interval to 18‑24months after a thorough review.

Are there dietary changes that boost medication effectiveness?

A high‑fiber, low‑red‑meat diet can reduce inflammation and complement NSAID therapy. Some patients benefit from a Mediterranean diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids, which may synergize with COX inhibition.

Ginny Gladish

October 4, 2025 AT 00:04The article presents a fairly thorough overview, yet it glosses over the nuanced risk–benefit calculations that are essential for personalized therapy. For instance, the cardiovascular contraindications of COX‑2 inhibitors deserve a deeper discussion, especially given the prevalence of hypertension in this patient population. Moreover, the references to trial data could be more precise; citing exact study IDs would strengthen credibility. Overall, the guide is useful but could benefit from a more critical appraisal of the cited evidence.

Faye Bormann

October 10, 2025 AT 03:16Honestly, while the guide is well‑intentioned, I have to point out a few things that many readers might overlook. First, the recommendation to start sulindac at 150 mg twice daily assumes perfect tolerance, which is rarely the case in real‑world practice. Second, the discussion of aspirin’s chemopreventive effect often omits the fact that adherence drops dramatically after a few months due to gastrointestinal discomfort. Third, the piece mentions emerging Wnt pathway inhibitors but fails to note the steep cost and limited availability outside of academic centers. Fourth, I’d caution against assuming that a low‑dose aspirin regimen is universally safe for teenagers; pediatric gastroenterology input is crucial. Fifth, the article’s monitoring schedule suggests colonoscopies every 12–24 months, yet patients with high polyp burden might need six‑monthly surveillance to catch rapid growth. Sixth, the side‑effect profile of celecoxib is downplayed, ignoring the FDA’s black‑box warning for patients with a history of myocardial infarction. Seventh, the piece briefly touches on dietary synergy but doesn’t explore the evidence behind omega‑3 fatty acids and their potential to augment NSAID efficacy. Eighth, the suggestion to combine NSAIDs with proton‑pump inhibitors is sound, but the long‑term implications of chronic PPI use, such as increased infection risk, deserve mention. Ninth, the guide could benefit from a clearer algorithmic flowchart that helps clinicians match genetic subtypes to drug choices. Tenth, the lack of discussion around renal monitoring for mesalazine, despite rare nephrotoxicity reports, is an oversight. Eleventh, the article’s tone is optimistic, but the reality is that many patients experience polyps that are refractory even to combination therapy. Twelfth, there’s no mention of patient quality‑of‑life metrics, which are increasingly used to gauge treatment success. Thirteenth, the role of patient‑reported outcome measures in tracking side‑effects is absent. Fourteenth, the guide states that “regular monitoring” is essential but does not define the exact lab panels needed for each drug class. Fifteenth, the emerging agents like LGK974 are promising, yet their phase‑II data still show a 30 % dropout rate due to adverse events. In short, while the guide is a solid starting point, clinicians need to fill in the many gaps before applying these recommendations wholesale.

rachel mamuad

October 16, 2025 AT 06:28i think the guide does a good job at mixing up the classic NSAID approach with the newer targeted therapies but i cant help but notice a few typos here and there. the mention of "low‑dose aspirin" as a chemopreventive agent is spot on, however the phrase "low‑dose aspirin" got written as "low‑dose aspirinn" in one spot. also, the term "Wnt pathway modulators" is used correctly, but later it says "Wnt pathway modultors" which might confuse some readers. overall, the jargon is solid – APC, STK11, COX‑2 – but a quick proof‑read would make it shine even brighter.

Amanda Anderson

October 22, 2025 AT 09:40Wow, this guide really hits the drama of living with polyposis head‑on. It’s like watching a thriller where the villain is a tiny polyp trying to outsmart the hero – the medication. The way it breaks down sulindac and aspirin feels like a backstage pass to the battle plan. I love the simple language that still packs a punch; it makes the whole thing feel less like a textbook and more like a conversation with a trusted friend.

Deborah Escobedo

October 28, 2025 AT 11:52Keep pushing forward you got this

Dipankar Kumar Mitra

November 3, 2025 AT 15:04Life is a series of choices, and when it comes to polyposis, the medications we pick become extensions of our own philosophy. Sulindac isn’t just a pill; it’s a statement that we won’t let the genetics dictate our fate. Aspirin, low‑dose and steady, reminds us that even the smallest daily rituals can shape destiny. Yet, we must also confront the shadows – the bleeding risks, the cardiovascular whispers – and acknowledge that every relief comes with a price. So, embrace the meds, but never surrender your agency.

Tracy Daniels

November 9, 2025 AT 18:16Great summary! 👍 Remember to involve a genetic counselor early on – they can really tailor the medication plan to your specific mutation and help navigate insurance hurdles. Also, keep a side‑effect diary; it makes follow‑ups with your gastroenterologist much smoother.

Hoyt Dawes

November 15, 2025 AT 21:28Honestly, this feels like a rehash of every textbook paragraph you’ve ever read, but with a sprinkle of hype. The “chemical scalpel” metaphor is dramatic, yet it doesn’t address the reality that many patients still end up on the surgical table despite drug regimens. It’s all very glossy, but the gritty details of adherence challenges are missing.

Jeff Ceo

November 22, 2025 AT 00:40While the guide is comprehensive, it’s vital to keep the patient’s autonomy at the forefront. Prescribing NSAIDs without a clear discussion about GI protection can be risky, especially for those with a history of ulcers. Clinicians should always ensure a shared decision‑making process.

David Bui

November 28, 2025 AT 03:52Honestly, the article’s tone seems overly optimistic about NSAIDs. In my experience, the side‑effect profile often outweighs the benefits, especially in patients with borderline cardiovascular risk. A more balanced view would help readers set realistic expectations.

Alex V

December 4, 2025 AT 07:04Oh, look, another “miracle drug” narrative. If you’re wondering why pharma loves to push COX‑2 inhibitors, it’s because they’re cash cows, not because they’re the silver bullet for polyposis. Remember, the devil’s always in the fine print of those clinical trial disclosures.

Robert Jackson

December 10, 2025 AT 10:16The grammar in this piece is mostly fine, but the use of “its” versus “it’s” is inconsistent. Also, the British spelling of “colour” would be more appropriate for an international audience. Lastly, the sentence about “low‑dose aspirin” could be clearer – the current phrasing is ambiguous.

Maricia Harris

December 16, 2025 AT 13:28Bravo for covering the emerging therapies, but honestly, most of us are stuck with aspirin and sulindac while the “new drugs” stay in labs. The drama around “phase‑II trials” feels more like a teaser than real hope.

Tara Timlin

December 22, 2025 AT 16:40Excellent breakdown! For anyone starting on sulindac, I recommend a baseline liver function test and a follow‑up at 3 months. Also, pairing the medication with a high‑fiber diet can help mitigate GI side effects.

Jean-Sébastien Dufresne

December 28, 2025 AT 19:52Very thorough article! 😊 Just a reminder: always check for drug‑drug interactions, especially if you’re on statins or antihypertensives – they can amplify side‑effects. Stay vigilant!

Patrick Nguyen

January 3, 2026 AT 23:04Comprehensive guide; ensure baseline labs before initiating therapy.